May 2022

Carbon Pricing Basics

Having set decarbonization targets for themselves in 2021, countries and companies will now need to work harder to achieve these targets. However, energy prices have been rising on the expectation that decarbonization will result in lower supply of fossil fuels, and this has also given rise to growing concerns about inequality as the burden of higher energy costs falls harder on the poor. From a macro perspective, it will be interesting to see whether this complicated mix of factors, which includes relations with Russia, will actually help to drive decarbonization, or whether it will constitute such a headwind for governments that it forces them to slam the brakes on stronger policy initiatives.

What is Carbon Pricing?

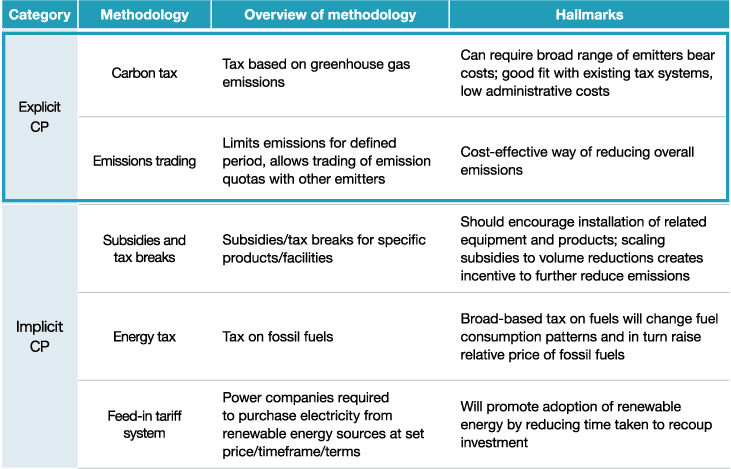

Carbon pricing involves setting a price on carbon, the main cause of climate change, to enable governments to impose a financial burden on companies commensurate with their carbon emissions. Carbon pricing can be broadly divided into implicit carbon pricing, and explicit carbon pricing which puts a price directly on carbon emissions.

Attention is focusing on carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes as the two most prominent forms of explicit carbon pricing. While both seek to reduce emissions, the variables controlled by the government differ.

Types of Carbon Pricing

Source: Nomura, based on Ministry of the Environment data

Carbon Tax (Price Approach)

In the case of a carbon tax, the government imposes a fixed tax rate involving a charge per ton of carbon emissions. Companies benefit from the ease of forecasting their cost burden given that carbon prices are fixed. This is why carbon taxation is referred to as the price approach to reducing emissions. The downside is the lack of visibility on how companies will react to carbon prices, making to hard to accurately forecast how much they would reduce Japan's total carbon emissions. We view the pricing approach of carbon taxation as a somewhat roundabout route to achieving global climate goals, given that these are usually stated in terms of quantity, such as the goal of becoming carbon neutral (net zero emissions) by 2050.

Emission Trading Schemes (Quantity Approach)

Emissions trading schemes enable governments to control the volume of emissions. Companies conduct economic activities based on government-determined emissions quotas, and can trade emissions credits on the open market in the event that they have surpluses or shortages. The total volume of emissions is fixed in advance, making this a direct approach to reducing a country's overall emissions. However, the price of the emission credits (ie, the carbon price) is determined by the market and therefore uncertain. From a corporate perspective, the downside is the difficulty of forecasting the cost burden from economic activity. In addition, the need to monitor (measure) emissions means that only companies that exceed a certain level of emissions can be covered by these trading schemes.

Carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes can also be deployed concurrently.

EU’s CBAM is scheduled to start operating from 2023

We should also pay attention to discussions surrounding the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a global carbon pricing system. The European Commission announced "Fit for 55" policy package in July 2021, which steps up initiatives for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in line with the EU's more ambitious 2030 reduction target (of 55% versus 1990, up from 40%). A particular focus in the policy package was the CBAM, which the EU cited introduced to prevent carbon leakage.

Carbon leakage refers to the import of goods from countries or regions with less strict emission constraints, which drive domestically produced goods (which incur costs related to cutting carbon emissions) out of the market due to superior price competitiveness and risks the hollowing out of domestic industry.

The CBAM is intended to apply the same carbon price to both domestic products and imports relative to their carbon content. The key point here is that carbon leakage is only an issue when countries or regions are taking inadequate initiatives on reducing emissions relative to the EU.

The EU intends to introduce the CBAM from January 2023. However, it designates the three years from January 2023 through December 2025 as a transition period which will mainly be used to gather data and inform the companies that will be reporting their imports. EU has already introduced free allowances to tackle carbon leakage under the EU ETS, which will gradually be reduced in line with the introduction of the CBAM. Imports in scope include cement, electrical energy, fertilizers, iron & steel, and aluminum.

Summary from “Japan begins discussions on carbon pricing framework” (February 24, 2021), “ESG Research: policy update” (July 16, 2021) and “Nomura ESG Monthly” (April 16, 2021).